|

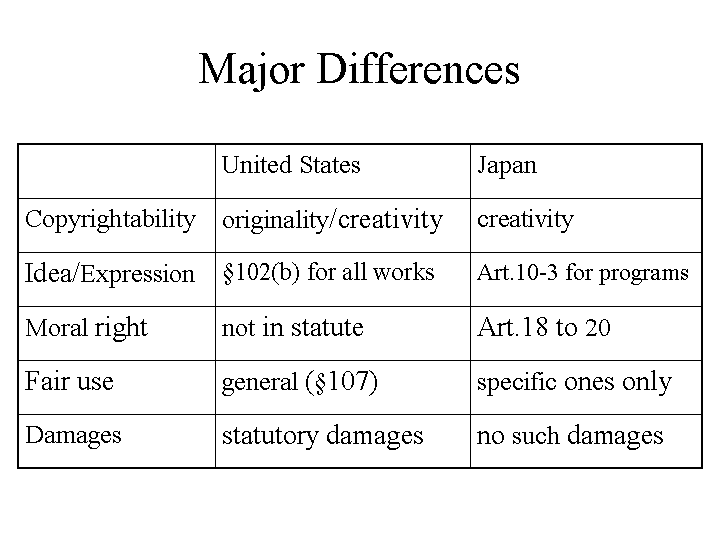

This is a chart which shows the major differences in both statutes.

Among copyrightablity requirements, the United States uses the concept

of “originality” which means “independent creation”

or “not copying” plus minimal degree of creativity. In Japan,

we only use a concept which corresponds to creativity.

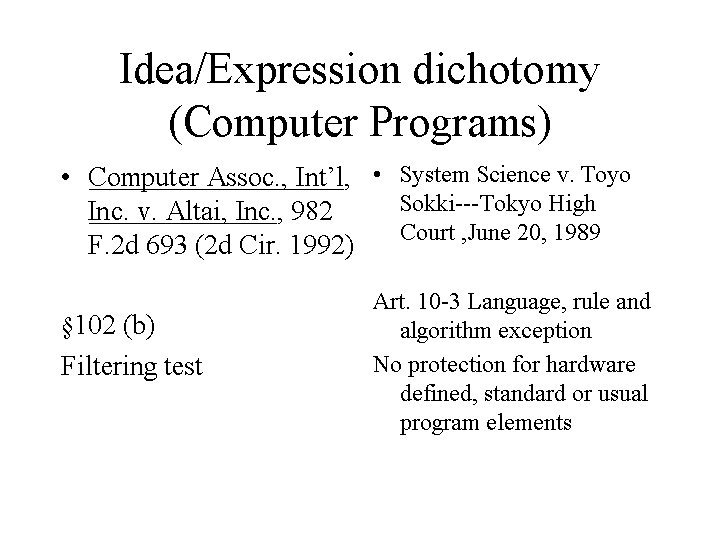

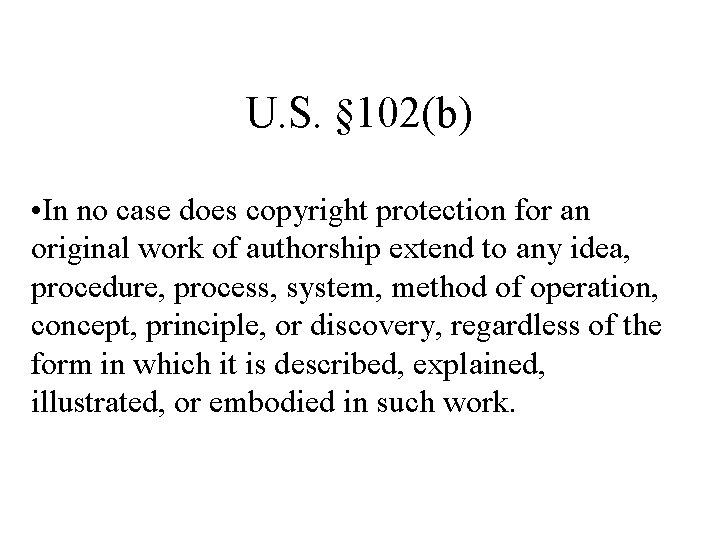

The U.S. law has a provision which clearly sets forth a so-called "Idea/Expression

dichotomy" in Article §102(b). In contrast, the Japanese law does

not have such provision, although sometimes the courts use the same kind

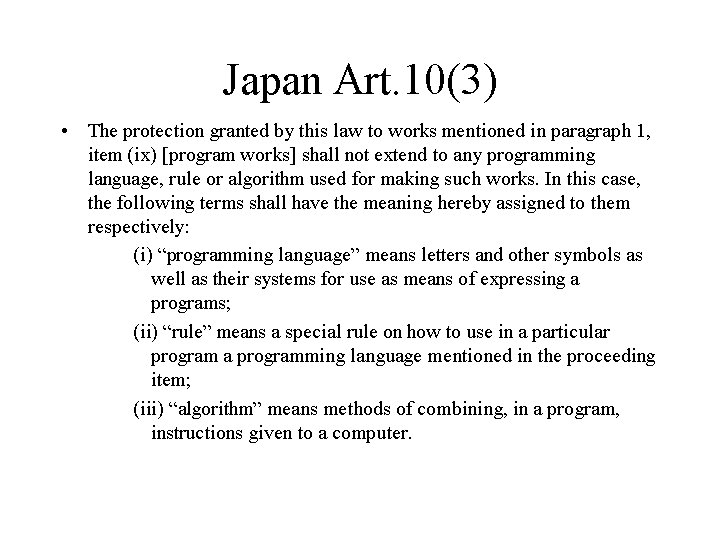

of principle. For computer programs specifically, we have a special provision

as I will explain later in detail.

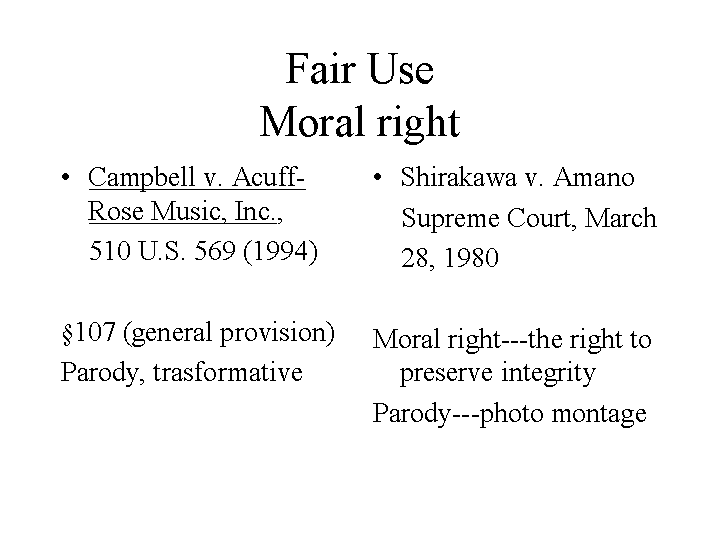

Even after the United States became a signatory to the Berne Convention,

the U.S. Copyright Act had no moral right provision except for Article

106A. The Japanese Act has moral right provisions in Articles 18

to 20, which are the right of making the work public, right of determining

the indication of the author’s name, and the right of preserving

the integrity of the work.

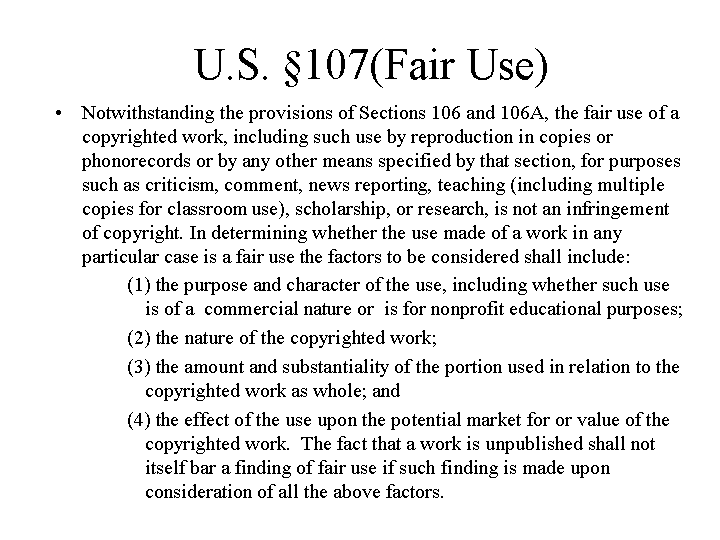

Next, the Japanese Act does have a set of detailed provisions specifying

fair use in particular circumstances such as reproduction for private

use or reproduction in libraries or quotations, but it has never contained

a general fair use defense such as in Article 107 of the U.S. Copyright

Act. This has caused a lot of difficulties in dealing with copyright cases,

as I will explain later.

The Japanese Act does not have statutory damages similar to Article 504

(c)(2) of the U.S. Code. This has caused a remarkable difference

in the amount of damages, as I will also explain later.

|